Name: Les Davison

Rank: Medic

Unit: 3rd Parachute Battallion

Regiment: 1st Parachute Brigade

After transferring to the 3rd battalion

around the first week in August 1944,1 found myself attached as medic with the

Headquarters company. The Medical Officer was a Capt. Rutherford and I knew some of the

other medics slightly, but now I cannot remember any of their names. As I was still a

member of the 1st Brigade things did not change much. We were constantly being either

briefed for the next possible operation, or being debriefed from the last one, which had

not come off.

After transferring to the 3rd battalion

around the first week in August 1944,1 found myself attached as medic with the

Headquarters company. The Medical Officer was a Capt. Rutherford and I knew some of the

other medics slightly, but now I cannot remember any of their names. As I was still a

member of the 1st Brigade things did not change much. We were constantly being either

briefed for the next possible operation, or being debriefed from the last one, which had

not come off.

We were stationed in Spaiding in Lincoinshire, a pleasant market town, and were billetted in what was a recreational park but which had been taken over for the duration. Our accomodations were Nissen huts which were notorious for being very cold in the Winter and warm in the Summer. Fortunately this was the middle of August and it was quite pleasant. Life went on pretty much the same, constant training and exercises, briefings for future operations and out on the town, either in the Pubs or at the Corn Exchange dancing, in the evenings.On the 8th September we were briefed for an operation, which, had it come off, would have been the biggest debacle in British Army history, fortunately, it was cancelled. However on the 15th September we were assembled in the briefing room once more. The plan was basically the same except the whole concept had been updated. D-Day was Sunday the 17th September, only 48 hours away. Every one was convinced that this operation would be cancelled too, however when we were confined to barracks it was pretty obvious that, finally, we would be on our way.Sure enough we were awakened early Sunday morning, told to pack our small kits and leave everything else in our kit bags. These would be taken by sea and delivered to us in Holland after the operation was over.

The previous evening, Saturday, the whole barrack room had participated in a marathon game of 'Brag'. This is a form of poker played with three cards. On the Saturday afternoon we were paraded and had to change all our money into British printed "Invasion Money" plus a nominal amount of each currency as our next weeks pay. These were French fancs, Belgian francs and Dutch Guilders. As this was the only money anyone possessed this is what we played for. I have always been pretty lucky at cards and consequently won most of the money in the room. As each player was wiped out they drifted off to their beds to sleep, knowing that we had an early call. Around midnight there were only four of us left and it was decided that we too would retire for the night as we had no idea when we might get another chance for a good nights sleep. I totalled up my winnings and, after converting it at the official rates, I found I had won the equivalent of Fifty-Six Pounds. This was about six months pay and I was rather elated. Whether I would ever get a chance to spend any of it remained to be seen, nevertheless I stashed it into my inside battledress pocket and was soon asleep.Reveille, as usual, came much quicker than I thought it should. After all it was only 6 A.M. and we were not taking off until somewhere around 11 A.M. Typical army, 'Hurry up and wait'.

After breakfast we paraded at 8.30 dressed in full battle gear and were told to stand easy. After about ten minutes we were told to fall out but not to leave the area. We lounged around for about an hour, doing the things soldiers do bes telling tall stories about their recent girl conquests. Finally dozens of 3-ton Bedford trucks lined up on the parade ground, and we started to embark. Our destination was Grantham, about forty miles away, where there was a large airfield presently occupied by the U.S. Airforce. 'Ah Ah' the veterans said, we are going with the Yanks aga. This was a reference to the time when they flew from North Africa to Sicily with U.S. Aircrews and quite a few of them were dumped in the sea.There were literally dozens of Dakotas all lined up in rows with their engines idling. We were assigned to specific planes immediately and started to emplane. There was much banter and horseplay as we were emplaning and, in retrospect, I think this was to offset the natural nervousness we all felt. None of us, of course, would admit that we were nervous and the horseplay was a cover-up. With a total of about 30,000 Allied troops being air-lifted from Britain to Holland within 24 Hours, roughly 60% Parachutists and 40% glider-borne plus the attendant fighter cover you can imagine the congestion in the skies that Sunday noon.

Third battalion was in one of the leading formations and for some time after becoming airborne, we circled until the rest of our flight joined us. With the formation complete we headed in the direction of Holland and it was an absolutely awe-inspiring sight to look out of the aircraft windows and see a never-ending line of planes, six abreast, with the fighters weaving in and out like mother hens. Each Dakota contained a "stick" of twenty men, all of whom carried, in addition to their personal kit and firearms, a kit bag or some other container. These would contain ammunition, grenades, food packs and, in my case, a kit bag full of medical supplies.

These containers were strapped to the soldiers leg so that he would be hands free whilst in the air. This was necessary so that he could control the drift of his parachute with the lift-straps. About 100 feet from the ground the container would be released and would drop and be suspended from the soldiers waist belt by a 20 foot line.To the unitiated this manouvre may seem a little hazardous, in fact we had learned in training that it was easier than jumping without any impediments. The reason for this was, when the kit bag hit the ground the chute was relieved of the extra weight and the landing was much softer. In Addition to the kit bag on my left leg I also had a metal collapsible stretcher attached to my right leg and when the time came to stand up, ready for jumping, I could barely move. I suggested to the medical sergeant that, because I could not move very fast, it might be better for everyone if I jumped last. He agreed and so I was last out of the aircraft when we jumped at 1.56 P.M. on the 17th September.

Our stick landed without incident and we were soon grouped with the rest of Battalion H.Q. on a heath known as Wolfheze. Apparently we were not expected as there was no firing of weapons and the whole thing seemed like another of the many training operations which we had been involved in England. Even the terrain was similar, which only added to the illusion.It took some time for the whole battalion to drop and, as we were one of the early arrivals, we had the unforgettable experience of watching waves and waves of planes disgorging the passengers and the whole sky seemed to be filled with parachutes. Finally the whole battalion was lined up ready for the march to the Arnhem bridge and still there was no opposition. We had about eight miles to go and it was now three P.M. (Four P.M. Dutch time) and the plan was to be at the bridge before dark. We moved off in the direction of the town of Oosterbeek, which is about three miles from the bridge and it was on the outskirts that we first came under fire. The Germans were finally reacting to the invasion and were organising their forces to stop our advance. The result was that we never got any further than the centre of Oosterbeek that Sunday and settled in for the night in a rather large house, which was still occupied by a local Doctor and his Wife.The company commander was trying to find out what was happening but our radios were not operating for some unknown reason so he asked the Doctor if the phones were still working. On being assured that they were, then asked if there was anyone the Doctor might know who lived near the bridge that we could telephone. Our host dialled a number and, after some conversation in Dutch, told us that the second battalion had reached the bridge and were holding the North end, however they were encountering very strong opposition and the enemy were entrenched at the South end and in pill boxes in the centre.

Early Monday morning the Battalion moved out down the main road to Arnhem opposition was minimal at first but as we approached the outskirts of the City we came under increasing fire and took to the houses for cover. The occupants were still in residence in most cases and were trapped, it would be suicide to venture outside. As we advanced slowly down the Utrechtseweg the fighting got heavier and casualties were mounting. We established Regimental Aid Posts, in the houses as we moved along and left one or two medics in each one. The plan was to move the wounded into the St.Elisabeth hospital after the situation stabilised, this was situated about a quarter of a mile ahead and was being used by the 16th Para. Field Ambulance as its main base of operations. Unfortunately the situation was so fluid that control of the hospital changed hands frequently and we never knew for sure who was in charge at any given time.Battalion H.Q. got to within 150 yards of the hospital and that was as far as we ever did get to the bridge. It was now late Monday evening and we were in danger of being surrounded by the enemy and cut off from the rest of the battalion. Just prior to this we had been visited by General Urquhart and his aide who had resorted to this method of communication as none of the Divisions radios were working. The powers that be decided that H.Q. would retreat, temporaly, but as we had 17 wounded in the basement of the house someone had to look after them.

Our sergeant medic said 'We need a volunteer to stay behind and look after the wounded and that's you Davison!!'. Not having much choice in the matter I resigned myself to the fact that I would probably be a prisoner of war in the very near future. I was left with a good supply of morphine ampoules, sulphanilamide powder and bandages and, of course, we each had our compo rations. We certainly weren't going to starve, although the compo rations were not very palatable. Oddly enough I did not feel hungry, there were hard boiled candies in the rations and constantly sucking on these seemed to alleviate any hunger pains.There was a constant battle going on outside which didn't subside until dark, and even then there was intermittent firing of small arms and the odd mortar bomb would explode in our immediate vicinity.

The wounded kept pretty quiet, wrapped up in their own thoughts as to their fate, and I kept them well sedated with morphine. It was my intention to try and get them to the St. Elisabeth Hospital as soon as conditions were favourable, however about two A.M. on the Tuesday morning I heard army boots right outside our cellar window. I should explain that our cellar abutted right on to the sidewalk and had a window below the ground in a window well which had an iron grate at sidewalk level.1 could see outside to some extent but could only look upwards. After hearing quite a number of boots clattering across the grating I looked up and discovered that they belonged to soldiers in field grey uniforms, obviously not our lot. I whispered, to the wounded who were awake, to keep very quiet as there were Germans outside and after about 15 minutes they had left and things became very quiet.

However just after dawn I saw boots running past our window again, two soldiers stopped right on the grating and I cautiously looked up to see that they were dressed in Khaki. I shouted to them, which gave them a bit of a fright, asking who they were. They replied 'South Staffs'. This meant that they were troops of the Glider-borne South Staffordshire Regiment who had dropped in the second lift of the operation on Monday. My spirits rose immediately as I figured we were now getting the upperhand. I informed my patients of the developments and this raised a quiet cheer. Obviously they were thinking that, maybe, they wouldn't be going to Germany after all. This hope proved to be short-lived. About 10 A.M. on the Tuesday morning there were khaki-clad soldiers outside our cellar again, unfortunately they were going the wrong way. I called up and said 'Who are you' the reply was again 'South Staffs'. It was obvious they had made an attack in the small hours and had been beaten back as soon as daylight arrived. So I decided that my strategy was to remain put until the situation stabilised, one way or the other. There was no point in trying to get these patients to the hospital, considering the racket that was going on outside, and most of them were reasonably comfortable. I kept the three most seriously wounded under constant sedation and they slept most of the time. These conditions pertained until, about two P.M., when everything turned quiet. I figured it was worth a recconaisance outside to see what the situation was.

I went upstairs to the main floor to discover that the occupants of the house had decamped, not surprising considering what was going on all around them, and went outside to see what was what. I discovered to my delight that we were in complete control of the surrounding area and immediately made my way to the hospital. There I found the senior medical officer and informed him of my situation. He said that everybody there was too busy to help and would I find some means of getting my charges to the hospital.Upon arriving back at the house, I couldn't believe my eyes, there, sitting right outside the front door was a jeep, with nobody in it, and, in addition, it had two collapsible stretchers stowed in the rear. Obviously it was a jeep that belonged. to one of the field ambulances. I got in the drivers seat and tried the starter, no joy, and decided that the distributor arm had been removed. This was the only way of immobilising a jeep as they had no ignition keys, and this proved to be the case. Normally I always carried a spare rotor arm with me, but for some reason I didn't have one. Having the use of the jeep was essential to my being able to evacuate my wounded, so I "borrowed" a ladies bicycle that I found in the house and started off down the line of battle, which was the Utrechtseweg from, Oosterbeek to Arnhem. I asked everyone I met if they had a rotor arm, no luck, until after about an hour, I found a jeep which had been hit by mortar fire. It was completely wrecked and I dug around until I located the distributor and removed the rotor arm. Happily I rode down to the house, with a red cross on my helmet, and red cross flags on the bicycle, only to discover that, in my absence the jeep had been completely destroyed.

I dumped the bicycle on the street and actually sat down and cried in frustration.After a few minutes I thought, well, I still have the problem of getting my wounded comrades into the hospital. I cycled down to the hospital and found a gurney (a wheeled stretcher) and pushed it down to the house. Taking the most serious wounded first, I proceeded to evacuate everybody to the St. Elisabeth. There was a constant battle going on all the time and it was quite dangerous, but I had no option, I had to get these people into the hospital. I had removed everybody but one by about 5 P.M. I put the last of my charges on the stretcher and started down the street, but before I got to my destination I realised that the situation had changed for the worse. The hospital was guarded by Dutch S.S. men and it was obvious that we had lost control again. By pure luck nobody had spotted us and 1 pushed the gurney into the last house on the street before the hospital. Fortunately my patient wasn't too badly wounded and was able to walk with assistance.We discussed the situation and decided that we would hide in the house in the hopes that our forces would finally prevail and we would eventually get him to surgery. We determined that there were no civilians in the house and decided to hide under the bed until we could decide what to do next. We spent most of the next 24 hours sleeping, with the exception that twice we were wakened by the sound of heavy footsteps, obviously army boots.

It's rather amazing but in each case nobody decided to look under the bed, both times it was German soldiers who tramped through the house and it was apparent that they were clearing the houses of our troops by going through each one to see if any were occupied.By about 10 A.M. on the Wednesday morning the fighting around the hospital area had quietened down considerably, with the Germans in complete control, and about this time we heard more footsteps which proved to belong to two Dutch doctors from the hospital, they went through the house calling out "Hollander! Hollander!" so we crawled out from under the bed and they told us that they had seen us go into the house the night before but that this was the first chance they had to come over. They told each of us to get on a gurney and then covered us completely with a white bedsheet. They said that they would try to get us into the hospital as if we were dead, otherwise we might be fired on by the Dutch S.S. who were guarding the hospital. For reasons which I have never understood, it seemed that the Dutch S.S. were much more vicious in their general conduct than the Wehrmacht soldiers. We set off across the road to the hospital and fortunately we had no trouble, we were wheeled straight into the chapel, which was being used as a mortuary. There were no Germans present so we hopped off the gurneys and I escorted my patient to the surgery where there was quite a queue of wounded waiting to be operated on. I informed the senior medical officer of what had happened to us and he said 'jolly good show!' and immediately put me to work in the wards. We were very short of medical staff and a two-shift system had been worked out, each shift being twelve hours. For the next ten days or so it was simply work and sleep.

All the beds were occupied and dozens of wounded were lined against the corridor walls, sleeping in their bed rolls. We had two well-known patients, Brigadier Lathbury and Brigadier Hackett. Both had removed their officers insignia and were referred to as corporal. Hackett was very seriously wounded, with internal injuries to his stomach, but Lathbury had only a leg injury, as far as I can remember, and he was quickly rescued by the underground forces. Hackett also was spirited away after he had recovered a little. The St. Elisabeth Hospital was run by German nuns, who stayed on and worked with us The medical forces of both sides worked together and there was no favouritism as far as who was next for surgery. The surgeons decided who were the more seriously wounded and operated on them in order. German or British, it made no difference.The battle was over on the 28th September, that evening about 2,000 of the original 10,000 who landed were evacuated across the Rhine to the forward Allied lines and the final batches of wounded were brought in from Oosterbeek, where the division had made its last stand. A couple of days later the Germans started evacuating all of us to Dutch barracks in Apeldoorn, about 20 kilometres to the North. They had decided that we would run our own hospital from these premises until such time as they were able to take us all to P.O.W. camps in Germany. The barracks were vacant but there were enough beds to accomodate all our patients. The Germans fed us, more or less, from a field kitchen. Watery potato soup twice a day accompanied by a slice of black bread and something called coffee, which I think was made of roasted grain of some kind. At least the German guards got the same food. so we could hardly complain. Soon the walking wounded were put on trucks and taken to Apeldoorn station. Here they were packed into cattle cars or freight wagons, with a little water and some dry bread, and carried off to P.O.W. camps. With the doors padlocked they had little chance to escape although I heard, after the war, that three of them had worked away at some rotten floorboards and made a hole large enough for them to drop through. They then went through the hole and dropped to the tracks and let the train pass over them.

After about two weeks the population of the barracks had diminished considerably. The ratio of medics to patients improved to the point that some medical personnel were offered the chance to escape, generally speaking R.A.M.C. people did not escape if there were wounded to look after but, as the wounded were evacuated, the medics were left behind in Apeldoorn with the result that there were more than enough to look after the casualties that were still there. Finally we were told that the barracks was to be closed down and that we would be on the last train to the Fatherland. Because the patients that were left were the most seriously wounded, the Germans had come up with a proper hospital train. This was a converted passenger train with all the seats removed and bunks installed down each wall of the coaches. If memory serves me right there were eighteen bunks on each side of a coach and each coach had an observation platform at each end. Fortunately for me the Allies knew we were in Apeldoorn station and kept bombing the line in front of the train with the result that we were there for three days. I had decided some time earlier that, if the opportunity presented itself, I would attempt to escape and consequently I kept one of the two sandwiches we were fed daily as a means of survival should I be successful in getting away. There was no chance to disappear while we were in the station as the whole train was guarded by about twenty S.S. men.

However when the train was moving I hoped that I would have no trouble getting off. I had talked to my charges about my escaping when I could and they all agreed that they would be allright and not to worry about them. Finally one evening about, the 10th October, the train started to move and I immediately started to put on my camouflage jacket and my small kit. There was a German medical orderly in the coach who had been working with me and it must have been obvious to him what I was going to do, however he made no attempt to stop me or raise an alarm. He was a typical, rather fat middle-aged German who probably hoped to get some leave when. the train got to its destination. Whatever the reason for his silence I was very thankful because I had had visions of trying to knock him out if he showed any opposition to my leaving. As I moved down the coach to the exit I whispered my goodbyes to the patients and they all wished me luck. Upon arriving at the observation platform I was surprised to see half a dozen of the medical officers on the adjoining platform, including my commanding officer, Col. Townsend. He asked me what my intentions were and I said I had been looking for him to ask for permission to escape. This was not really true as I had decided to jump anyway, but as it was expected that an escaper would get permission it suited my purpose to tell a white lie. He immediately said it was O.K. and that the officers had decided that one of them would escape. They had drawn straws to decide who was the lucky one and a Captain Theo Redman had won the draw. I had never met this officer, who was a surgeon, but Col. Townsend suggested we go together and this suited me fine. It was decided that we jump together, one from each side of the train, and as there were guards on the roof of each coach with machine guns, the other officers started a mock argument in order to distract them. I stood on the bottom step of the platform until I felt a tap on my shoulder and promptly jumped to the side of the track and rolled down into the ditch.

I laid low until the train was out of sight and apparently we had not been seen by the guards as no gunfire erupted. After a minute or so I called out across the track "where are you sir" and the Capt. whispered 'over here', he was directly across from me. We were in a thickly wooded area so I crossed over the rails and we had some discussion as to what we would do. We had no idea where we were although I knew the train had been travelling North, so I suggested we travel due South, avoiding the roads and populated areas in the hopes that we would eventually reach the Rhine and swim across. Capt. Redman wanted to know how we would know whether we were going South, I said I had my escape compass (All allied airmen and parachutists carried an escape kit with them in an oilskin pouch, this contained a silk map of the area, in this case North-Western Europe, a small compass about the size of a thumb nail, a couple of trouser buttons which were magnetised, and would make a compass when balanced on a needle which was included along with some thread.) which I had secreted in what I shall call a rear orifice when we searched by the Germans. He said "Good for you" at least we will have some idea where we are going.So we set off through the woods, not really knowing what to expect as we had no idea where we were, until after about an hour we came up against a barbed wire fence about seven feet high, it was the type that angles out at the top and we couldInt decide whether we were on the inside or the outside.

It didn't take long to find out as we heard dogs barking in the distance, fortunately we were on the outside of the fence. Because the fence ran East to West we turned to the West hoping to get around it and after about a quarter of a mile it turned to the South. Because the dogs were making such a racket we quickly got away from the area, which was just as well as I found out after the war that this was a military area.We carried on with our march until about 11 P.M. when we came across a house in the woods. There were lights on so we stopped about a hundred yards away to discuss the situation. Capt. Redman suggested that possibly we should change our plans and try to contact the Dutch underground. I agreed and, because we didn't know where we were, he also suggested that he creep up to the window of the house and see if they were talking Dutch. The Capt. spoke German as he had trained in Germany before the war and for all we knew we might be in Germany. When the Captain came back from the house he said they were not speaking German and he could only conclude that they were speaking Dutch. We approached the house with some trepidation, not knowing what our reception would be like. I knocked on the door which was opened slightly by a middle-aged man of slight build who promptly slammed the door in our faces. After a minute or so I knocked again and a young girl opened the door and,in very good English, asked what we wanted. She obviously recognized us for what we were and quickly invited us in.In the house was the man who opened the door at first, together with a jolly looking rather plump lady and two younger children. The older girl who had let us in was the only person who spoke English and asked us if we would like some coffee and a biscuit. We accepted this although we were both ready for a good cup of tea. We never saw any tea for the next three months.

The coffee was 'ersatz', I don't know what it was made from but it certainly wasn't coffee, however we were very grateful for it. We told the girl how we came to be at her house and she spent some time telling the rest of the household our story. After a few minutes with her parents the girl said we could sleep in the haystack for the night and that she would try to contact someone from the underground. She said that her family was not active in the resistance but had a way to contact people who were and she would do that first thing in the morning.The haystack in the yard was about 20 feet high with a roof over it but no walls. The girl showed us where a wooden extension ladder was kept and we scaled the ladder and got into the hay, after which we pulled the ladder up after us and laid it across the top. Soon we were both asleep in no time and it only seemed a short while before I heard the girl coming to us softly that it was time to come down and have some breakfast. After a typical Dutch breakfast of cold ham and a hard boiled egg with black bread we were asked to follow the girl into the woods and keep a distance of 100 metres behind her in case she was stopped by soldiers or the "Green Police". If we spotted any strangers or police we were to immediately split up and go in opposite directions and try to hide. Hopefully in this manner she may be able to deny any knowledge of us because the consequences of being caught hiding escaped prisoners was that all the family would be shot at once and the farmhouse burned down. After we had walked about half a mile the girl stopped and waved to us to do the same. She then came back and told us we had just walked over our hiding place. I was a little nonplussed as all I could see was fallen leave and twigs.

When the girl came back she scraped around with a broken branch until she stooped down and pulled on an iron ring, up came a wooden trapdoor about two feet square and beneath it was a hole about twelve feet by twelve feet square and about the same depth with a wooden ladder running down. She said we would have to stay in this place until someone could contact us, probably this evening, but not for sure. She also promised to bring us food when she could. Down we went and were surprised to see that we would be quite comfortable as there was a sofa, an easy chair, a carbide lamp and a radio, some candles and a metal pail for toilet purposes. She asked us not to play the radio as it might be heard above ground and as we had nothing to read, all we could do was talk about what might happen and eventually slept. About two P.M. the trapdoor opened and our guardian angel handed down some bean soup and a vacuum flask of ersatz coffee, she also said that someone would come at about seven o'clock so that we would not be afraid when the trapdoor opened. We wolfed down the food and spent the next hour or so speculating on who might come and what would happen afterward. Right on cue about seven P.M. the trapdoor opened and down came a rather Ascetic looking man, tall, and dressed completely in black. He wore glasses and even had a black hat. I thought he might be an undertaker but it turned out he was a Calvinist minister. We, of course, stood up when he entered. He surveyed us warily for a few seconds then asked us to please sit down. In heavily accented English he started to ask us questions about everyday events in Britain, the answers to which would not likely be known by a German who might be masquerading as an escaped prisoner. He had not introduced himself nor asked us who we were, but had in dicated that he was in touch with the underground forces. We were learning the procedures of the "Onderduikers", nobody said who they were and the reason, of course, was, should anyone be captured, re-captured or apprehended in any way, the less they knew, the less they could reveal.

After a few minutes of questioning he said that he was satisfied as to our identity and would we please show some identification just to be on the safe side.

We both produced our army paybooks and after a good look at these he said he would provide us with accomodation and contact with the resistance forces

who would look after our welfare from then on. He said we should call him Nico (short for Nicolas) and that he had three bicycles outside,

unfortunately the two you will ride on have no tires. Please stay back from me about 100 metres and if I am apprehended simply ride past and

ignore me and if you are stopped God help you,' because I will not be able to. Nico had told us that there was a curfew from 8 P.M. and

that we must complete our journey by that time. He didn't say how far we had to go or where and as it was now 7.30 P.M. it apparently

was not far.After about 20 minutes of hard riding ( it's very hard work riding a bicycle with no tires) we turned off the road into

the semi-circular driveway of a rather large house and stopped at the back door, which led into the kitchen. We dismounted and Nico

ushered us inside with the warning to be very quiet.

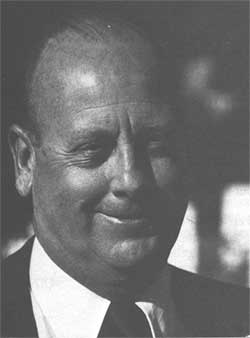

photo: Nico and Lena 't Hart I had figured Nico to be about 32 or 33 years old and when we entered the kitchen we were introduced to two

ladies, Lena, Nicols wife, and a younger lady who was Trijnkje, their maid. There was no further discussion and we were quickly taken

up the back staircase to the attic, which was unfinished except for the floor. This was strewn with apples and corncobs and was obviously

the place where their winter supplies were kept. However a small part had been cleared and here were two camp cots, already made up with

sheets and blankets, two kitchen chairs and a small card table. Nico anticipated our question about toilet facilities and presented us

with a rather large chamber pot. We were to use this, hopefully only for urination, as there was only one bathroom in the house and this

was on the ground floor.We would be informed by Nico or Lena when it was safe to come downstairs because the house was, in fact, the

vicarage and there was a constant stream of visitors to see the 'Dominee'. It was crucial that our presence there was kept secret as

not every Dutchman was on our side. Nico soon suggested that, as we were probably quite tired, that maybe we should retire for the night

and talk again in the morning and mentioned again that we should be quiet when moving about and talk quietly. Personally I was happy to

fall into a bed and was asleep within minutes and I am sure that Capt. Redman did likewise.

After a few minutes of questioning he said that he was satisfied as to our identity and would we please show some identification just to be on the safe side.

We both produced our army paybooks and after a good look at these he said he would provide us with accomodation and contact with the resistance forces

who would look after our welfare from then on. He said we should call him Nico (short for Nicolas) and that he had three bicycles outside,

unfortunately the two you will ride on have no tires. Please stay back from me about 100 metres and if I am apprehended simply ride past and

ignore me and if you are stopped God help you,' because I will not be able to. Nico had told us that there was a curfew from 8 P.M. and

that we must complete our journey by that time. He didn't say how far we had to go or where and as it was now 7.30 P.M. it apparently

was not far.After about 20 minutes of hard riding ( it's very hard work riding a bicycle with no tires) we turned off the road into

the semi-circular driveway of a rather large house and stopped at the back door, which led into the kitchen. We dismounted and Nico

ushered us inside with the warning to be very quiet.

photo: Nico and Lena 't Hart I had figured Nico to be about 32 or 33 years old and when we entered the kitchen we were introduced to two

ladies, Lena, Nicols wife, and a younger lady who was Trijnkje, their maid. There was no further discussion and we were quickly taken

up the back staircase to the attic, which was unfinished except for the floor. This was strewn with apples and corncobs and was obviously

the place where their winter supplies were kept. However a small part had been cleared and here were two camp cots, already made up with

sheets and blankets, two kitchen chairs and a small card table. Nico anticipated our question about toilet facilities and presented us

with a rather large chamber pot. We were to use this, hopefully only for urination, as there was only one bathroom in the house and this

was on the ground floor.We would be informed by Nico or Lena when it was safe to come downstairs because the house was, in fact, the

vicarage and there was a constant stream of visitors to see the 'Dominee'. It was crucial that our presence there was kept secret as

not every Dutchman was on our side. Nico soon suggested that, as we were probably quite tired, that maybe we should retire for the night

and talk again in the morning and mentioned again that we should be quiet when moving about and talk quietly. Personally I was happy to

fall into a bed and was asleep within minutes and I am sure that Capt. Redman did likewise.

We were awakened about eight A.M. by Lena who had brought us some breakfast. This consisted of sliced ham, sliced cheese and black bread, there was coffee of the ersatz kind but at least the milk was real. Lena could not speak English and simply smiled, put the tray down and went back downstairs. Nico came up to see us about an hour later and we talked for some time about the prospects of our getting back to the Allied lines. He said that soon an active member of the resistance would come to see us and he would give us any news about the prospects for our getting back. Nico also told us that, although he was connected with the 'onderduikers' he was not an active participant and simply let his home be used as a safe house. He had with him a road map of Holland and, for the first time since we jumped off the train, we could see where we were. Nico and Lena lived in the village of Wapenveld and he was the Minister of the Nieuwe Kerk. The church was right next to the house and we were told that we would hide there, in the roof, whenever there was any likelyhood of a raid (razzia) by the Germans. As it turned out we were to be the guests of these very brave people for about six weeks during which time Theo taught me how to play chess and we read a lot of English books, which were provided by the numerous members of the underground who visited Nico regularly. Twice during this time we had to go into hiding in the church roof. The ceiling of the church was made of four inch tongue and groove wood and the only access was through a trapdoor cut into it. When we got word that a raid was imminent, Nico, Theo and I would go into the church , get a long wooden extension ladder, which was kept there for the purpose, and use the top of the ladder to push the trapdoor out of its hole. We would then scamper up the ladder and pull it up after us into the roof space. This space had a wooden floor and contained two kitchen chairs, a small table and two narrow mattresses along with a battery-operated radio and two milk bottles full of water. After the emergency was over Lena would come into the church and give us the O.K. to come down. If Lena came into the church quietly singing a certain hymn, this meant that, although the Nazis had left the church, they were still in the immediate vicinity and we must keep very quiet. Some evenings Nico would invite us downstairs, into the parlour, where we would play some harmless card games, or Theo and I would play chess against Nico. Once or twice a week we would have visitors from the underground who would converse earnestly, in Dutch, with Nico for maybe half an hour after which Nico would translate what was said. Mostly we were told how the war was going and sometimes we would get some word on a possible scheme to get us back to the Allied lines. Twice we were alerted to be ready to move the following evening, but in both cases nothing happened.

After about three weeks an unusual incident occurred which enlightened us as to why we had to be so quiet in the house. As I mentioned earlier there was only one bathroom in the house and this, situated on the ground floor adjacent to the kitchen, was a busy place. One afternoon Lena called upstairs that the way is free to go beneath". This was her way of telling us that the bathroom was free and there were no strangers in the house or expected. I told Theo that my need was rather urgent and he said, alright you go first. I had only been in the bathroom about two minutes when someone tried the door. I immediately sensed that something was wrong so I kept very quiet. After a few seconds the handle was tried again, however I kept quiet until Nico came to the door and said it was alright to come out now. He told me to go upstairs quickly without any explanation as to what was going on. The next evening we were informed that the person who had tried the bathroom door was an elderly Jewish gentleman. This man had been hiding from the S.S. and had been with Nico and Lena for some months. It was his custom to have a short walk around the grounds of the house and church after lunch every day and it was during these outings that we had the chance to use the facilities. However it appeared that on the previous day he had been seized with an urgent desire to use the bathroom, after he had only been out a few minutes and on being confronted with a locked door he had become rather agitated. He could see Lena and Trijnkje in the kitchen and heard Nico working in his study, so he probably thought "who is in the bathroom?". He apparently came to the conclusion that someone else was hiding in the house as, the next morning, he set out on his bicycle and was not heard from again until the war had ended.

After our mysterious "onderduiker" had left it made our lives a little less constrained. We were able to use the bathroom more frequently although we still dare not go downstairs without permission from Nico or Lena. It also allowed us to spend most evenings in the parlour with our hosts. The electricity had been turned off by the authorities and the only light we had was produced by a canister of carbide, about the size of a one pound jam jar, with a hole in the top. The addition of a small amount of water would produce a gas which issued from the hole and which could be ignited. A small white flame was produced and this was the sole source of light. It was enough however to illuminate the chess board and provide Lena with light to read.Theo and I, of course, were very anxious to hear news of our impending move and the days seemed to drag on, when finally, a gentleman whose name was Mr. Doktor but in fact was a baker, informed us that we should be ready to leave the following evening about 7 P.M. The next evening we said our goodbyes to Lena and Nico and were told by the courier "Henk" to follow him in the usual fashion.100 metres to the rear and to ignore him if he was stopped by the authorities. We mounted the same bicycles we arrived on, no tires, and set off in the rain with raincoats covering our uniforms. We had no idea where we were going, and had learned not to ask.We were told only what we needed to know, this being the method adopted by the underground forces to protect themselves in case any of their charges were picked up by the S.S. or the "Green Police" (these were Dutch police who were collaborating with the Germans). and was based on the fact if you didn't know, then you couldn't tell, even under the most extreme torture. We pedalled doggedly for about an hour with no problems, we were very obvious as the tire-less bicycles made a hell of a racket on the cobblestone roads. However because of the heavy rain add the fact that it was now after the curfew hour of eight o'clock there was no one else about and we were not challenged. It was about this time that we got a scare. We were riding on a two lane highway and a German Army truck, travelling in the same direction, slowed down to our speed. The soldier in the passenger seat leaned out of the window and asked Theo, who was on my left, for directions to Amersfoort. Fortunately Theo could speak German but hadn't the foggiest idea where Amersfoort was. So he gave them some meaningless directions and, to our immense relief the truck went on its way.

It was some time before my heart stopped pounding. About one A.M. 'Henk' turned into the driveway of a very large house and ushered us inside. We were very surprised to find the place crawling with Airborne soldiers from the various units that had fought at the Battle of Arnhem, R.A.F. types who had been shot down and evaded capture and a few other odd characters who were on the run from the Germans. Theo immediately recognised some of his fellow medical officers, among whom was Capt. Lippman Kessel, a surgeon from South Africa and Major 'Shorty' Longland, another surgeon. Naturally there was quite a bit of reminiscing by all of us mainly as to how we had escaped and where we had been in the meantime. We were also told that we would be there overnight and given some food. We were to try and get some sleep, wherever we could find a place on the floor, as it might be some time before we got another chance. The next evening, as soon as it got dark, we were packed into various vehicles, some of which had been stolen from the Germans, and started on a journey South towards the Rhine. We had been briefed earlier that we would be taken as close to the river as was prudent and from there would march to the Rhine where boats from the other side would be waiting for us to ferry us to safety. The road trip was uneventful, if somewhat uncomfortable, and after about an hour and a half we turned off into a wooded area and told to disembark. We formed up in single file and, as it was pitch dark, held onto the coattails of the man in front. When everybody had arrived, there were about 120 of us we moved off due south through thick woods with instructions to keep quiet, no talking and no smoking. I estimated that we were about 25 miles North of the Rhine and it was now Nine P.M. We had five hours to get to the river if we were to be on time. This would be sufficient if we simply had to march this distance, but walking single file through woods and having to take numerous detours to avoid enemy posts, it was obvious that we would be very late. We could only hope that our friends from the South side of the river would wait for us.

In the event it didn't matter as, after about an hours walking, we suddenly heard machine gun fire ahead and everyone scattered in every direction. Four of us ran together to the east and after about a quarter of an hour stopped to discuss our situation. There was a Capt. Noble, a Scottish medical officer, two Sgt. Glider Pilots and myself. We decided that as we didn't know where we were and the fact that there was a distinct possibility of our running into German patroll we had better hole up somewhere and try to contact the underground again. We quickly found a cowbarn and settled in on the upper floor under the hay. Everybody was soon asleep, and in no time, or so it seemed.I was awakened by movement in the barn below. It was six-thirty and I silently crawled over to the hole in the floor from which the hay was dropped down, very carefully I peered down into the stable area and saw a rather tall Dutchman who was preparing to milk the cows. I said, in a conversational way, good morning and the startled farmer looked up quickly to see who was speaking. It was apparent that he was aware of what had happened the night before as he did not appear to be too surprised to see me.

By now the others were awake and they all showed themselves to the farmer. He said that he did not speak much English but got the message across that he would bring us some food. Within ten minutes he was back with a shopping basket filled with ham and cheese sandwiches and a jug of fresh milk with four mugs. He indicated that he would bring someone to see us after he had finished milking and asked us to stay where we were and keep quiet as he didn't want any of the farmhands to know we were there. We spent the morning talking quietly amongst ourselves, discovering who was who and what had happened to them since their escape. By pure coincidence it turned out that one of the Glider Pilots was called Geoffrey Mallinson and came from my home town of Keighley in Yorkshire. His father was the manager of the Yorkshire Penny Bank where I had an account. Around noon our friendly farmer came with lunch which consisted of delicious soup and black bread. He told us, as best he could, that someone would come in the afternoon and that we would be leaving. We thanked him for his hospitality but he indicated that it was the least he could do for the liberators of his country....Around three P.M. a lone bicyclist came and introduced himself as a member of the "Onderduikers". He told us that we would be split up and would go to different families who had agreed to take us in until some other plan was devised for our eventual return to the allied lines. He asked who would like to go first and, as the two Glider Pilots wanted to stay together, and Capt. Noble said he would go last, I went with this man, who I now know as Jan ter Wal, on the crossbar of his bicycle. We travelled along forest footpaths and side roads for about three quarters of an hour and finally came to a small village, where we stopped at a typical Dutch residence and I was ushered inside. I was introduced to the family which consisted of Ma and Pa, four sons and a maid, only two of them gave me their names, these were two of the teenage sons, Jan and Fokke. It turned out that these two were the only active members of the underground in the family, but, in effect, it didn't make much difference if you were active or not if you were found hiding escapers. The penalty was a shot in the head for the whole family and the burning of the house. I found myself constantly amazed at these brave people, especially when I discovered that there was a small contingent of German soldiers billetted only a few doors away. The head of the family was the manager of the local public baths and consequently had frequent dealings with the 'Moffen' (derogatory slang for Germans). In fact some of the German non-commissioned officers would come in for coffee in the mornings while I would sit in the living room,in civilian clothes and pretend to be the "deaf and dumb cousin from Amsterdam.

Like most of the Dutch people who helped us, the Dijkstra's (I only learned their name after the war) were very religious and we always said grace before meals with a short reading from the bible afterwards.On the only Sunday I was with them I was left at the house with the oldest son while they all went off to church. Also on that same Sunday afternoon, Jan and Fokker asked me if I would like to accompany them on a walk in the woods. I suggested that this might be dangerous for all of us but they pooh-poohed the idea and said not to worry as they were well-known to the local soldiers and I had already been accounted for as the cousin from Amsterdam. It was quite an experience to be walking around and nodding to the Germans whom we met frequently. After being with the Dijkstra's for about ten days, Jan ter Wal came and spent some time talking with the family, after which he told me to get my things as we were going to another safe house. I asked if there was a problem and he said yes, the Moffen were making frequent raids trying to find the escapers who had been ambushed on "Pegasus Two". Pegasus One was a similar operation, a few weeks earlier, which had succeeded. The Germans were making house to house searches as they were aware that about one hundred of us were in the vicinity and it was obvious that we were being hidden by the local populace. In view of this it had been decided that I would be safer in some other place, quite some distance from where I was. Consequently I left with Jan, on the crossbar of his bicycle again, and rode in this manner for about 15 kilometres to a farm, which I found out after the war, was in the village of Scherpenzeel.

When we arrived I was surprised to find two paratroopers already in residence and also this place was Jans hideout. I was introduced to the family, Wynand, the farmer, his Wife Maagi and two boys whose names I have forgotten. The two para's also introduced themselves. They were Sgt. Keith "Tex" Banwell and Vic Moore, a private from the 1st Battalion. These two had been there for two weeks, since immediately after the Pegasus Two ambush. We three Para's slept in the chicken house and spent our days helping with the farm chores, it was the least we could do, considering that Wynand and his family were risking their lives and property by hiding us. A few days after I had arrived we were told that there was a Razzia going on in the area and that we would have to go into the woods at the rear of the farm right away. The S.S. were constantly making raids on the farms and houses, rounding up all males between 16 and 65 for work on the defenses on the River Ijsel. They also probably hoped to find some of the escapers in the process. We were all dressed in coveralls and wearing "Klompen" (Dutch wooden clogs), so that we became part of the landscape when working outside in the fields. Jan, who was the only Dutch person at the farm who could speak English, said that we should run quickly into the bush at the rear of the farm, split up and hide wherever we could find a suitable spot. This way, if the S.S. caught anyone, the others had a good chance of being undetected. Whilst running across the ploughed fields, which were quite muddy, I lost one of my wooden clogs, I then stepped out of the other one as it was impeding my progress, picked both shoes up and ran with them into the woods. Maagi, Wynands wife, and the children stayed in the farmhouse whilst an S.S. Officer and four other ranks searched the house thoroughly to no avail. Jan told us afterwards that Maagi and the children had been questioned at some length, by the S.S. Officer, as to the whereabouts of the farmer and apparently convinced him that he had already been taken away for forced labour.

After the raid the farm returned to its usual routine, which included numerous visits by various underground members who used it as a meeting place to plan their sabotage raids against the Germans. It was also used as a resting place and safe house for Onderduikers and escapers on the move. A frequent visitor was 'Willems' who was a Captain in the underground army and leader of the local group. I have known Willems as Henk van Bentum since 1969, which was the first time I had attended the annual re-unions and remembrances of the Battle of Arnhem. These are held always on the weekend after the 17th September, which was the date of the original drop. Henk began a small transport company after the war which grew into one of the larger trucking companies in Holland and retired some years ago. Both Henk and Wynand were honoured by the American people for their work in hiding and assisting U.S. flyers to escape. They were presented with special medals and certificates of appreciation by President Carter in Washington D.C. Our evenings on the farm were spent discussing ways and means of crossing the Rhine, which was about 20 kilometres to the South, as we knew that the South Bank of the river, in this area, was held-by Allied troops. However this was not going to be easy as all civilians had been evacuated from an area approximately ten kilometres paralell to the North bank of the river and this area-was, in effect, the front line of the battlefield, heavily populated by German troops of all kinds. Any attempt to get to the river and swim across, which was my own answer to the problem, meant passing through these enemy forces without being detected. Willems, Jan and other underground members, would be part of these conversations from time to time and tried to convince us not to try it alone. They said, without the help of the underground as guides we would surely be caught and thus would endanger their organisation and themselves. Their fear was that we would be interrogated and probably tortured into revealing where we had been hiding for the last three months.

The underground were in touch, by radio, with the Allies and were positive that another attempt to ferry the escapers and evaders across the river would be made soon. Two previous actions had met with two completely different results. "Pegasus One" was the code word for the first scheme to repatriate the numerous evaders who were wandering around the countryside immediately after the battle. About 150 were gathered in various hiding places and around the end of October were ferried across the Rhine by Allied troops from the South side under covering fire. "Pegasus Two" was to be a similar operation whereby a about 120 escapees of all kinds, Paratroopers, Allied airmen who had been shot down and glider pilots, were going to be ferried across the river. This operation, of which I was part, has been described earlier in this narrative and was a complete disaster, due, I understand, to someone giving the whole game away to the Germans. Jan and Willems were insistent that we not try to get home alone, but I was equally insistent that I wanted to be home for Christmas. I pointed out that, as there were no immediate plans to get us across the river, we should be allowed to try. They finally agreed that we could try on our own, however this brought up a problem, Vic could not swim and I had half promised him that I would not go without him. Our problem was solved the next day when one of the "Onderduikers" brought us a one-man rubber dinghy. This had been retrieved from one of our aircraft, which had been shot down in the vicinity, and was just what we needed. Tex, Vic and I unpacked it, blew it up with the attached hand pump and put it in the duck pond. However when we all tried to get in it promptly sank and it was obvious that all three of us could not get across the river in one trip. As two trips were out of the question it was decided that Vic and I would go and Tex would stay behind and take his chances with the resistance.

(Editor: Sgt. Keith (Tex) Banwell was captured. He then escaped from a train after knocking out his guards. Making contact with the Dutch resistance again, helping them out planning the succesfull ambush of German troops, wiping out an entire unit. Tex was an ex-commando and ex-member of the Long Range Desert Group. More details about 'Tex' who became very famous and is the record holder of most- jumps can be found elsewhere on this website. 'Tex' died at the age of 80 in july 1999 and was saluted by his comrades with a traditional maroon barets on his funeral.)

After some discussion with Jan and Wynand it was decided that we would leave the next evening, December 5th, and that Wynand would take us on bicycles as close to the river as possible, after that we would be on our own. The next evening, after saying our goodbyes to the family and Jan, we set off with Wynand in front in the usual fashion, Vic carrying two fence posts and myself carrying a burlap sack with the boat in it. After about a half hour Wynand stopped and waved at us to come to him. We were at a T- junction of the main Utrecht-Arnhem road and a much narrower road running South. Wynand pointed down the small road, said, "Daar is de Rhine", shook our hands and wished us the best of luck. Vic and I carried on, riding our tire-less bicycles for about another 15 minutes, at which point we were challenged, out of the pitch blackness, with the words, 'Wer Dah!!". I took this to be the equivalent of our "who goes there" and motioned to Vic to keep quiet and ride like hell. However I suppose Vic was so excited about being so close to getting away, that he shouted something unprintable at the challenger who promptly started firing a rifle in our direction. It was apparent that, as we could not see the sentry, he could not see us as it was very dark and sleeting. We pedalled as hard as we could and, fortunately, there was no hue and cry and the firing stopped. I suggested to Vic that we should dump the bicycles as the noise, made by the tire-less wheels, was quite loud. We were obviously right into the enemy lines and probably would not be so lucky next time we encountered any of them. He agreed so we dumped the bicycles in the ditch and started walking. This of course, slowed us down considerably and it soon got to Five A.M. with no river in sight.

We discussed our situation in view of the fact that it would soon be getting light and decided to find a place to hole up. Our intention was to carry on as soon as darkness fell. We soon found an abandoned farm and went into the deserted cowshed and up into the hay on the second floor. Having been walking for most of the night we were soon fast asleep. I was awakened by the sound of voices and gingerly looked down into the cowshed. What I saw was not encouraging, to say the least. About a dozen German soldiers were down there standing around talking and smoking. Why they were there I have no idea, but I quickly put my hand over Vics mouth and motioned him to keep quiet. We lay there for about two hours, hardly daring to breathe, until finally about two P.M. they all formed up and moved out. With a rather large sigh of relief we decided that some food was in order. Maagi had made up three sandwiches for each of us, black bread as usual, We decided to eat two each, just in case we had any further problems and were unable to make it across the river that night. As soon as it was dark we moved out. We kept to the fields but basically followed the road, which ran due South. Although we were well within what must have been the enemy front line, we were not challenged again and about 11 P.M. arrived at the dyke. Up we went, over the dyke road running along the top and started down the other side towards the river bank. The dyke was covered with small trees and bushes and we made quite a racket getting down to the river bank. We got quite a shock when we arrived at the bottom. There was a towpath running alongside the rivers edge, this was for the horses that towed the barges up and down the river. What we had not been prepared for was the fact that there was a sentry walking up and down the towpath, he in turn connected with another sentry about 100 metres to the East and on the return trip connected with a sentry 100 metres to the West. We had to assume that this sequence continued for some distance in each direction so there was no hope of going around them. Whilst hiding in the scrub at the bottom of the dyke Vic and I discussed the situation quietly. It soon became obvious that the only way to get into the river was across the towpath. The question was, what were we going to do about the centries?

Finally I had an idea. Sentry duty in the British Army is two hours on and four off. If the Germans used the same system it was possible that the sentries would change shifts at midnight. So,possibly, the changing of the sentries would give us our chance to cross the towpath and be on our way. We waited breathlessly for about 40 minutes and, sure enough, at midnight the sentry marched off to what I can only presume was some sort of guardhouse and left the path clear for us. We squirmed our way across the path and attempted to inflate the boat with a compressed air cylinder which was attached. However the thing made such a noise that I turned it off immediately and finished inflating the boat with the hand pump. We threw it into the water and Vic climbed in. I then slid into the water and started to push the boat into the current by swimming behind it with my hands on the stern. With Vic paddling with the fence post and me swimming behind we made good progress and there was no activity from the shore. Apparently we had got away without anyone hearing us and the only problem we had now was the current, which had strengthened considerably. It was sleeting and the water was quite cold. However because of the exertion required to push the boat and possibly the fact that we were fully clothed, I didn't feel the cold at all. We had been in the water about half an hour and still couldn't see the other bank, I was getting worried that, maybe we were not making any North to South progress but were just drifting with the current. I had been told it was about 400 metres across, if this was the case we should have been over to the other bank by now. It became obvious that we were making very little lateral progress and I just prayed that we would not be swept back to the North Bank. All we could do was keep paddling and pushing, and we just tried a little harder. Our efforts were rewarded when Vic shouted that he could see bushes on the South dyke and within minutes I could feel the bottom.

After reaching the bank we pulled the boat out and started to climb the dyke, we soon reached the dyke road, which ran across the top and then we had to decide whether to walk East or to the West. Our problem was that, although we knew that the Allies were in control of the South side of the river in the immediate vicinity, we didn't know just how far that control ran, and at this point, because we had been drifting downstream, we didn't know really where we were. After some discussion we decided to walk to the East, this decision being based on the on the presumption that we had been drifting West. After some time we came to a 'T' junction with a road running to the South, which, fortunately, had a signpost pointing South which said Nijmegen 20 Kilometres. We knew that the allies were in control of Nijmegen and literally whooped with joy. Unfortunately our enthusiasm was dampend a little when we got to the bottom of the dyke. The road to Nijmegen was under about three feet of water, we were not aware that that the Germans had blown the dyke walls in order to force the Allied forces back from the river. Nevertheless this only slowed us up a little. We could see where the road was by the telephone lines at the side of the road and the feel of the tarmac under our feet kept us on track. We had a length of string with us so we tied this to the boat and dragged it along just in case the water got too deep. It was rather hard work walking through waist-high water and consequently our progress was quite slow. Before we knew it we could see the glimmerings of dawn and decided that, as we didn't know for sure that we were safely in Allied territory, we had better find a place to hide. This had been a well-populated area and we noticed that we had passed quite a few abandoned farms, so we didn't have any problem finding a place to take cover. As it happened we were quite close to a small village which, I found out after the war, was called Zetten. We picked the biggest house, which was two-storey red brick, and made our way up to the second floor, as the water was half-way up the walls of the downstairs rooms. All the rooms had been emptied of furniture and of the three bedrooms upstairs two were empty. However the third bedroom was locked and it didn't take much imagination to figure out that this was the place where all the house furnishings had been stored.

Although we knew that this was a home of the same Dutch people who had risked their lives to help us, we broke into the room and just hoped that they would forgive us in view of the circumstances. The bedroom was stacked to the ceiling with the belongings of the occupants and also contained a fireplace. As we were soaking wet and quite cold, we went through all the cupboards and drawers to see what was available. Vic found a man's suit but all I could find was a ladies tweed skirt and jacket. We stripped off and dried ourselves on some bed sheets we had found and decided that if we could get Vic's cigarette lighter to light we would make a fire in the fireplace and dry our uniforms. In the event we didn't need Vic's lighter as we found some matches and used some underwear as kindling to get a fire going with smashed furniture. It was getting quite light now, about 6.30 A.M. when I noticed there was a harmonium piled among the furniture. Vic and I wrettled it out to a relatively clear space and I started to play. I could play an accordian so the harmonium wasn't much different. You might think that this was quite risky, but we were pretty confident that we were in Allied territory and we hoped it might bring our presence to someones attention. After about 10 minutes Vic signalled to me to stop playing as he thought he had heard something. Sure enough we could hear a motor. In order for you to appreciate the situation, here we were, two British paratroopers, one dressed in a business suit and the other in a ladies two-piece, on the top floor of a house with three feet of water in it, in a small village in no-mans land. Nothing but water as far as we could see and the strains of 'Roll out the barrel' coming from an old foot pump harmonium. It's hilarious when you think about it.

I rushed over to the window where Vic was and we both listened with some trepidation, to what was obviously a motor vehicle. The question in our minds was, what kind of vehicle would be operating in three feet of water and, secondly, was it ours of theirs? About ten seconds later we got our answer. An Allied D.U.K.W. (an amphibious jeep) came round the corner with ten or so Canadians aboard. We started shouting 'over here , over here", and the D.U.K.W. quickly made a beeline for us. All the Canadians had their rifles trained on us, so we put up our hands and waited until they got to the house. They nudged the craft right up to the wall of the house directly under the bedroom window and the Captain in charge of the patrol asked us who we were. We told him, in as few words as possible, who we were, how we had got there and why we were dressed in this fashion. His reply was 'well get your things and we'll take you to Headquarters in Nijmegen and we will soon see who you are'. When we got to Nijmegen we were allowed to take a shower and given some denim fatiques to wear until they decided what to do with us. After a good breakfast of Spam and eggs we were taken into separate rooms. A Canadian captain, apparently an intelligence officer, then asked me to go over my whole story, whilst a male stenographer took it all down. I told him everything from the minute I parachuted into Wolfheze, our dropping zone, until that morning. The only thing I left out were the names of the Dutch people. All this took about two hours and I noticed from time to time, the Capt. shaking his head, apparently in wonderment.

When I had finished I was left in the room, under guard, for some considerable time. I can only assume that the two interrogators were comparing notes to see if there were any discrepancies in our stories. Eventually the Capt. came back, dismissed the guard and told me he was satisfied with my story. He gave me an authorisation to go to the quartermasters store and get a complete new issue of military clothing. He also said that Vic and I would be going by transport first thing the next day to Brussels and flown home from there to Northolt Park aerodrome. When we arrived in the U.K. we were met by a provost sergeant who gave us train vouchers to our respective homes and told us that we had been granted three months leave. Apparently this was mandatory for all returning prisoners. We were also given Ten pounds each against our back pay. Naturally we both wanted to inform our relatives of our return as we knew that we would have been posted 'Missing in action'. I found a pay phone and rang the neighbour of my Sister-in -law and asked her if she would please go next door and bring my Sister-in-law to the phone. The neighbour didn't ask who was calling and when my relative, said 'Hello' I said 'Hi! Annie, it's Les!". She said Les who?. I said "your Brother-in-law Les Davison, I just got back from Holland. Annie said" Oh my God, we all thought you were dead". I said I wouldn't try to explain now on the long distance phone but would she please tell my Mother and everyone in the family that I was home and would be seeing them the next day. So ended one of the most exciting periods of my life and, as you can see by the foregoing story, one that is etched into my mind even after all these years.

Editor: And here ends an exiting story! Les lives in Ontario, Canada. He deceased on February 14 2013. Les is also mentioning Theo Redman in his story. Theo Redman's story is also in the 'veterans memories' section on this website!

- Theo Redman died of cancer in 2004.

- Tex Banwell died on July 25, 1999 of Parkinson.

- Vic Moore was a private in 1st bat. He had a pub on the Isle of Man after the war and died in 1997.